Napoleon as quoted by Metternich, Volume I page 312

He said to me one day in 1810, on the occasion of a long conversation in which he had just given me the history of his life: ‘I have clouded and obstructed my career by placing my relations on thrones. We learn as we go, and I now see that the fundamental principle of ancient monarchies, of keeping the princes of the reigning house in constant and real dependence on the throne, is wise and necessary.’

Metternich, Volume IV page 313

January 10, 1826. — The first need in every country being the clear and precise determination of the line of succession to the throne.

Metternich, Volume IV page 319

June 8, 1826. — The claims of the historian begin with the separation between the periods.

Had Napoleon confined his plans to the preservation of what the Republic had conquered, he would have greatly increased his popularity; his warlike temperament carried him much further. He was a born conqueror, legislator, and administrator, and he thought he could indulge all three inclinations at once. His undoubted genius furnished him with the means of doing so.

Raised by the Revolution to the summit of power, Napoleon endeavoured to prop up by monarchical institutions the throne he had made for himself. The destructive parties, having to do with a man equally great as a statesman and as a general, who knew his country and the spirit of the nation better than any who ever guided the destinies of France, were above all anxious to save from the wreck of their works all they could secure from the encroachments of the Imperial power.

The future of American Conservatism is the Federalist Party because this it is the de facto party of Lincoln by virtue of the fact it embodies the spirit of annexation.

Lincolnian annexation is the antidote to the reigning confusion on the Right brought about by its bizarre devotion to the always failing strategy of secession because annexation is the exact opposite principle of secession.

Secession failed because secession did exactly what its very definition promised it would do which was to secede (naturally!) all of the governing institutions to the Wilsonians.

In addition to the oddity of no series of endless defeats for secession ever being endless enough to shake the faith of the cult of secession, another peculiarity is how universal this error is across the entire spectrum of American Conservatism – from the extreme to the mainstream – with the lone exception being the Federalist wing of it.

By extension, whereas failure as grave and false as secession can only generate an equal proportion of exhaustion, confusion and complexity, the opposing force of annexation produces the virtues of energy, clarity and simplicity.

Secession, the very foundation of all non-Federalist branches of modern American Conservatism, is a lie, which makes every non-Federalist variant on the Right a lie.

Annexation, the old Lincoln Right to be renewed again, is the most solid foundation because annexation is truth.

Once grounded firmly on the solid ideological foundation of annexation follows a perspective broad enough to reveal the complete systems engineering blueprint for why American governance is malfunctioning.

To lay out this schematic the noble Federalist program of annexation first looks to the various governing points of control, which have been seceded to the Wilsonians, and are destined for annexation once more.

The Hamiltonian strategic map divides American political infrastructure into these basic control points (Although this list may not be 100% complete, it is broad enough for our immediate purposes) –

(1) Hamiltonian governmental institutions (e.g., the military-industrial complex, the Federal Reserve, Wall Street and the banking sector generally).

(2) Wilsonian governmental institutions (e.g., the various Federal bureaucracies, academia, public and private unions).

(3) Political parties and their elected office holders.

The difference between good Hamiltonian government and bad Wilsonian government is entirely a function of how these points of control are organized.

Under the pre-New Deal order of Hamilton, Clay, and Lincoln the American System is primarily organized around executing the policies of Hamiltonian Capitalism and the classic functions of government via their power over the above control points.

Both the Hamiltonian institutions and (what would later be known as) Wilsonian institutions are servants of Hamiltonian Capitalism and Hamiltonian governance because both institutions are responsible for implementing policy, not deciding policy.

Hamiltonian Capitalism and governance exercise control over these points mostly in one of two ways –

1) By vesting elected officials (who should be largely financially sponsored by and, therefore, be agents of Capitalism) with the power to immediately fire any employees of any government agencies these elected officials have been given executive responsibility for by a legislature (either state or federal).

2) By placing non-governmental entities in the private sector (such as media companies) under the ownership of private individuals or businesses that are biased in favor of Hamiltonian Capitalism.

Through this simple arrangement Hamilton achieved a government that would primarily (but not exclusively) serve the interests of Capitalism and the business classes.

The New Deal system has completely derailed proper government functions by reversing this virtuous structure of governmental control.

Instead of Capitalism controlling the bureaucracies through elected officials, Wilsonian maldesign gives bureaucracies control over Capitalism and Hamiltonian governmental institutions through the total bureaucratic control of elected Democrat politicians and through the bureaucratic hampering (as much as possible) and even the coopting of any resistance the bureaucracy encounters from elected Republican politicians.

The New Deal achieved this governmental monstrosity by warping the operations of the control points through a complex series of policies sold under the disguise of “Reform” of the corruption of 1865 to 1929 Golden Age Capitalism (wrongly called “Gilded Age”). But this “reform” only resulted in a Progressive system many orders of magnitude worse than that produced by the greatest excesses of the pre-New Deal spoils system.

Indeed, this has resulted in disastrous policies that were unheard of under Cold War era Communist states such as the modern Progressive tolerance of public hard drug usage and rampant homelessness.

In the case of government agencies, the control points went haywire by breaking the elected official-government worker-supervision framework with policies that made government workers and agencies de facto independent of the will of elected officials and, by extension, independent of the voters. Most importantly, this freed the federal and, in most cases, state government workers from any meaningful oversight of their work. These policies included making it extremely hard to fire individual bureaucrats and almost impossible to fire large numbers of bureaucrats at the same time.

In the case of (officially, if not in practice) “non-government” institutions such as academia and media other elaborate policies made them independent of normal Capitalist incentive structures. For example, the political power of hyper-Wilsonian academia is artificially inflated by regulations protecting universities with near-monopoly power over job credentialing for the most profitable career paths. This monopoly prevents alternative job training career routes from gaining traction with students and employers, despite the fact there is no reason the vast majority of knowledge shared to prepare students for jobs cannot be delivered outside of a university setting.

In another example of a non-governmental institution having its control mechanisms fail, in the early decades of television New Deal inspired broadcast licensing regulations arbitrarily limited the number of broadcast channels available (and, hence, limited the number of options for television news) to only a handful of conveniently centralized outlets that all had pro-New Deal news propaganda; and any Federalist devotee gives zero credit to the fact that Progressive propaganda was in this era delivered in a more professional manner than today because of the hard work of celebrated, widely admired, Wilsonian conartists like Walter Cronkite.

With the later appearance of cable channels government regulations further protected supposedly “private”, but still government-dependent, propaganda outlets through anti-competitive measures such as cable bundles that propped up what would have been unsuccessful Progressive news outlets by unnecessarily tying them in a package with vastly more lucrative channels such as sports.

Although the entire explanation and history of how Wilsonian control mechanisms operate in each institution is very complex, at the most essential level they all involve reversing Capitalist and elected official control of the governmental institutions, thus, placing them all under the control of Wilsonian bureaucracy.

Therefore, the modern project of the Federalist Party is nothing more or less than to revert the entire American political system from Wilsonian to Hamiltonian by restoring Capitalist control of the Wilsonian institutions, – i.e., by Capitalism, or, partisans of Capitalism annexing all of the Wilsonian institutions.

The result of Capitalist annexation of the Wilsonian system means the automatic implementation of all Hamiltonian Nationalist policies from immigration restriction, to trade protectionism, to a pro-military-industrial complex foreign policy.

Since this project will involve a great deal of restoring democratically elected official control over the bureaucracies we will call the process of Capitalist annexation of the Wilsonian institutions “democratization.”

And by “Capitalism” we mean Gordon Gekko Capitalism; the genuine, 120 proof version of economic Darwinism complete with arms smuggling to third world conflicts, strip mining environmental reserves for natural resources, and fossil fuel industry world domination.

Of course, putting Wall Street, corporations and the wealthy back in control of the bureaucracy sounds extremely counter-intuitive to any non-Progressive considering how many of the wealthy are either outright Wilsonian partisans or the most tepid possible opponents of it.

Nevertheless, it is a unambiguous certainty that restored Capitalist control would result in this absolutely complete change in policy and governance because the individual wealthy are not relevant.

What is relevant is that the Hamiltonian infrastructure is a completely intact, completely operational system (despite appearances to the contrary) that only needs to be liberated from its crackpot Wilsonian opponent machine with which it operates in parallel to, and, in perpetual conflict with.

Beyond even this, the institutions to be annexed are simply assets, which need nothing more than to be annexed and reorganized.

That includes annexing the most seemingly worthless institutional assets, such as the Republican Party which itself is a total failure: A failure which makes it a perfect asset to acquire.

Any Progressive political desires among the rich or squeamishness from wealthy non-Progressives (as distinct entities from the highly valuable political assets and infrastructure they control) is completely irrelevant.

Afterall, Hamilton’s National System is, by definition, Nationalism.

However, annexing such an enormous amount of Progressive institutional assets (which, if the American Progressive movement were measured as a single economy, would be valued in the trillions of dollars) means onboarding and managing them.

Clearly it will not do to simply annex this enormous amount of assets!

It is equally necessary that it be organized and managed properly.

In order to accomplish this we come to the main topic of this work: The division of powers.

Although this idea has existed in some form since recorded history began, the division of powers is a decidedly 18th century concept known to Hamilton because it was that century when it was refined into its most coherent form.

Understanding the concept of division of powers is of the utmost importance because the control points Hamilton designed cannot be restored without knowing how the various points should interact.

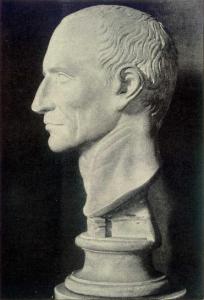

However, in order to understand Hamiltonian division of powers we are going to direct much of the focus of this work not to Hamilton but to his contemporary, the counter-revolutionary and 18th century Imperialist, Metternich and his understanding of European Monarchism.

There are two reasons for this.

First, because America’s political project is an entirely European political project.

Of course, mentioning this fact will horrify both Europeans and Americans about equally. Regardless, it remains true: Without the European Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries the United States would still be some kind of Puritan theocracy run out of Boston. And ever since 1776 the flow of ideas across the Atlantic has always rippled both ways with a Lord Keynes swaying America as much as an Alfred Thayer Mahan captured the attention of Europe. Therefore, we will look to European Monarchism to find that its commonalities with American politics are as important to understand as are the points where the founders wanted to diverge from traditional European governance.

The second reason for looking to Metternich is that while reading Metternich years ago it occurred to me that the Austrian Empire (and its predecessor before 1806, the Holy Roman Empire) he served also operated under a division of powers system.

And Austria was somewhat more of a unified state than the Holy Roman Empire was, with both having their own constitutions –

The Imperial Diet (Reichstag, or Reichsversammlung) was not a legislative body as is understood today, as its members envisioned it to be more like a central forum, where it was more important to negotiate than to decide.[216] The Diet was theoretically superior to the emperor himself. It was divided into three classes. The first class, the Council of Electors, consisted of the electors, or the princes who could vote for King of the Romans. The second class, the Council of Princes, consisted of the other princes. The Council of Princes was divided into two “benches”, one for secular rulers and one for ecclesiastical ones. Higher-ranking princes had individual votes, while lower-ranking princes were grouped into “colleges” by geography. Each college had one vote.

The third class was the Council of Imperial Cities, which was divided into two colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. The Council of Imperial Cities was not fully equal with the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The representation of the Free Cities at the Diet had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation was formally acknowledged only as late as 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years’ War.

To any modern Westerner the way power was divided in the Austrian Empire and Holy Roman Empire appears significantly more complicated than the relatively straightforward three-way division of national powers in the United States.

In the various roles Metternich held, he carried out his duties in a divided power system that was governed not only by written laws but also by ancient traditions and unwritten customs that were equally important in finely balancing how different power centers, such as the Imperial Diet, the Catholic Church, regional authorities, local aristocrats, the Emperor (or Empress) of Austria, the business classes, and so on, balanced their power with the powers of others.

Indeed, for his entire career Metternich himself was a power center in his own right despite the fact he was never the Emperor of Austria.

In his view these various institutions, though interrelated, were never to have their functions confused with eachother, and he went to great lengths to never confuse their different roles.

In this way, and despite the fact he had no faith at all in the ability of average citizens to run the Empire, his judgement that elite centers of power should be distinct, with well-defined functions based on law and unwritten traditions, never fused together, and respected for fear of upsetting the balance of power among elites, does share a fundamental organizing principle closer to the US Constitution than it does with the totalitarian, centralizing, 20th century ideologies.

In fact, the American creation of an Electoral College was probably directly inspired by the existence of Electors in the Holy Roman Empire.

Division of powers, that great art form of statecraft that so influenced the 18th century mindsets of both Hamilton and Metternich, was forgotten because of the politics of the 20th century.

The 20th century distorted humanity’s understanding of good governance because its three, distinct, dictatorial ideologies – Communism, Nazism, and Progressive Bureaugarki – involved merging every institution together with the state.

In addition, although they never got the opportunity to implement their ideology in the real world, extreme Libertarians of the 20th century made the same mistake in reverse by thinking that (rather than merging the economy with the state) all governmental institutions should be merged into, or have their functions replaced by, Libertarian economic systems.

What they failed to understand was that if the state abdicates its traditional duties and powers to private sector businesses, then businesses themselves would begin to misbehave like governments because their new governmental powers would be abused in the same way regardless of which institution – private or public – held them.

The powers of government itself are what tempt those who possess them to misuse them, not the institutions per se that hold them at a particular time.

Therefore, completely merging the state’s duties with the private sector simply transfers the exact same temptation of corruption previously held by the state to private entities, who will in turn corruptly use those powers in the same way as traditional governments.

But whether one prefers to merge everything with the state, or, if one prefers to merge everything with the free market, approaching political philosophy with an attitude of merging everything together, by definition, means adhering to a philosophy without any concept of division of powers.

The idea of effectively keeping distinct and separate institutions distinct and separate is a completely foreign idea to all Westerners born after 1932 who have no living memory of any political debate that wasn’t dominated by the idea of politicizing and merging everything with the state; even the most inconsequential matters down to the very last pronoun, carbon atom, e-cigarette and plastic straw.

And what debate there has been post-1932 about division of powers has been burdened by confused arguments made by a laughably weak American Right unable to manifest a firm power balance structure out of their hazy, usually contradictory, understanding of the ideas behind it.

But the Federalist Party agenda requires embracing the idea of division of powers because Hamilton’s Capitalist economic system was built as the master of a division of political powers and, therefore, cannot be properly restored without that understanding.

And so we begin our journey into unleashing the great occult energies of the Federalist Party through a rediscovery of this long-forgotten design principle.

To this end we will define the scope, theories to be discussed, and types of government.

Then we will proceed with a discussion of division of powers as practiced in Monarchical systems of government to better understand America’s balancing mechanisms.

Afterall, most of the effort of the founding founders to establish a division of powers centered around restraining the powers of the head of state because this is historically the most natural point where an autocracy would try to centralize itself.

It is with a thorough understanding of Monarchy, and whatever restraints were imposed on the ruler be they de facto or de jure, that we can appreciate Hamilton’s division of power system in a new light.

First to the statement of scope –

Scope Statement – This work is concerned only with a Hamiltonian perspective on the Constitution’s system of division of powers that came out of Philadelphia in 1787, and which Hamilton played the decisive role in persuading the states to ratify. Any alternatives that Hamilton proposed but which did not end up in the final product are outside the scope of this work.

Now to define theoretical concepts to be discussed, which are –

Oligarchical Spectrum Theory – This is the theory that no true Autocracy or Democracy has ever behaved, or ever can behave, in their purest forms because there are always multiple people who have have outsized power to influence, even veto, the actions of the most absolute dictator in an autocracy. At the same time, the number of people with genuine power to consistently affect government policy in a well-planned way (instead of reacting temporarily to events like rioting peasants) is always fewer than the number of eligible voters in a democracy. Instead, Autocracy and Democracy are the degree to which Oligarchy skews towards the will of one person or, on the other side of the spectrum, towards the will of the people at-large. But, in practice, neither Autocracy nor Democracy behave like the literal, definitional, extremes of Autocracy or Democracy because they must always remain along the spectrum of oligarchy.

The Classic Functions of Government – The classic functions of government are defined as those roles which every civilization and philosophy that has ever existed (except two) agree are legitimate powers of the state, e.g., the power to enter into treaties with foreign nations, the power to mint currency, the power to pass and enforce laws, the power to tax, the power to provide for the common defense by raising a military, etc, etc. The only two exceptions are extreme Libertarians and Anarchists.

Efficiency of Representation Theory – This is the theory that governmental powers are best executed if they are vested with some kind of representative with the appropriate skills to carry out a process on behalf of the nation instead of the nation deciding on every measure and proposal, as is seen in mass Democracy. Imagine how completely unmanageable diplomacy would be if every negotiation with a foreign power had to be conducted with constant voting on each clause, instead of a head of state simply giving the process of negotiation to individual diplomats.

Shareholder Theory – Derived from game theory, this is the theory that groups of people coordinate to support, or oppose, systems to the degree they benefit, or not, as “shareholders” in the success of the system.

Turning to the primary types of government, they are defined as Autocracy (the rule of one), Oligarchy (the rule of the few) and Democracy (the rule of the people).

What these three terms share in common is their complete inadequacy because they are too general and group together different subtypes that function differently from others within the same overall group.

Consider Oligarchy. The “rule of the few” could refer to the post-Stalin Soviet Politburo where a few dozen top politicians ran the government.

However, “the few” could also mean 1% of a nation’s population hold the power to govern.

In the latter case, even 1% of a medium to large sized nation would mean that the ruling oligarchy consists of hundreds of thousands to millions of people. This oligarchy would find decision making harder to coordinate than the Politburo model because the Soviet Government could get a better, nearly immediate, feel for where the few important decision makers were leaning on various issues than could an oligarchy with many thousands to millions of members. An expansive oligarchy would, simply for coordination issues, need to have a representative system of some kind (perhaps a republic, but not necessarily) where the main factions within the ruling class selected politicians who best represented their interests.

Despite an oligarchy of 1% requiring more complex operational requirements compared to an oligarchy of a few dozen people, both are categorized under the broader category of “Oligarchy.”

Which means the definition of Oligarchy is entirely unsatisfactory on the grounds that the definition fails to define.

Likewise, Autocracy and Democracy are also inadequate for being excessively broad.

Clearly, there needs to be a more thorough definition of the subtypes within the general categories of Autocracy, Oligarchy and Democracy. Each of these subtypes will be defined by their distinct characteristics and functions that separate them from their other subtypes.

Refining these three, excessively broad, terms we present the major subtypes of Autocracy, Oligarchy and Democracy.

Autocratic Subtypes

Autocracy – Any type of rule by a single leader.

Monarchy – Rule by a single leader selected by hereditary descent, unless that leader is the founder of a dynasty or chosen by other elites to found a new hereditary dynasty. In the case of a founder of a Monarchy who was not born into royalty (e.g., Napoleon) they qualify as a monarch only if they take power and establish Monarchy’s hereditary system of power transference through their own bloodline.

Autocratic Theocracy – Rule by a single religious leader. Power is normally transferred from one religious leader to another religious leader.

Autocratic Militocracy – Rule by a single military leader. Power is normally transferred from one military leader to another military leader.

Oligarchical Subtypes

All of these subtypes, except Aristocracy, select their members through some sort of election/nomination process within their respective oligarchical systems and members usually possess some sort of power to expel members from leadership.

Aristocracy – Rule of leaders selected by hereditary descent and where any monarch has powers that are either well-defined and reigned in the aristocrats, or the monarch’s powers are merely figurehead in nature (a successful historical instance of this kind is the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth). Power is normally transferred from one aristocrat to another aristocrat.

Theocracy – Rule of religious leaders. Power is normally transferred to other religious leaders.

Militocracy – Rule of military leaders. Power is normally transferred to other military leaders.

Meritocracy – Rule of those who deserve to lead, or deserve to vote for leadership based on ability and knowledge. This system is oligarchical in nature if eligibility for leadership is narrow. Who qualifies as deserving to lead or vote will tend to vary across time and across nations. If eligibility is broader it becomes more democratic in nature. An example of a very narrow Meritocracy would be the Catholic Church where the Pope is elected by an elite set of priests in the College of Cardinals. Because Meritocracy tries to give leadership and voting rights only to those who deserve it, the percentage of the population that is eligible to vote and/or lead is never set at a fixed number: For example, if the right to vote is granted for military service then more of the population would be eligible to vote after a war than after a long period of peace.

Progressive Bureaugarki (AKA Progressivism AKA Bureaugarki) – Rule of the bureaucrats.

Democratic Subtypes

Mass Democracy – All citizens are eligible to vote, with few to no qualifications required to be part of the electorate.

Direct Democracy – All governmental policies require the entire electorate to vote in favor of them before they can become policy.

Meritocracy – Rule of those who deserve to lead, or deserve to vote for leadership. This system is democratic if eligibility is broader across the entire population.

Keep in mind that all of these subtypes of Oligarchy and Democracy are defined as they are because they are skewed in favor of certain members of society and certain ways of holding and transferring power, but they can never achieve the pure form that their names suggest.

For example, there was a never a Militocracy in history where wealthy business leaders did not also have some sort of significant de facto and/or de jure ability to influence the decisions of their nation’s military leadership.

In the case of the British Empire it was both aristocratic and meritocratic because its ruling class not only included hereditary aristocrats but it also was flexible enough to elevate commoners who displayed a high degree of talent. Likewise, many oligarchical military governments in Cold War era Latin America included input from the business classes in decision making.

The worth of all these systems of government is judged by how well they perform the classic functions of government.

In order to determine which system, and under what circumstances, best carries out these functions the attitude the analyst should start with is the engineer’s attitude, which is that of strict neutralityuntil we have studied the various systems in detail.

If the best government can be achieved by pulling a rabbit out of a hat then we should not hesitate to put on white gloves and a tuxedo to draw a rabbit out of a tophat and award the startled bunny with the nuclear launch codes – a surprise that will no doubt be met with the greatest joy and wonder from our esteemed rabbit.

Underlying the classic functions of government is an inherently democratic assumption.

That democratic assumption is that the classic functions of government exist to serve the collective benefit of the entire demos.

This assumption is absolutely fundamental to every government in history, and must be at least superficially acknowledged by even the most tyrannical kings, emperors, and dictators: Regardless of what Hitler and Stalin thought and said in private, in public they always deferred rhetorically to this democratic precept by justifying their policies on the basis that they “represent the people”; that their policies were, overall, best for the people.

So did the most iron-handed monarchs before the 20th century.

There is no, or almost no, historical example of a tyrant who was so absolute that they would seriously challenge the assumption of democratic legitimacy in public by saying their policies were detrimental to the people but they were proceeding anyway because it is good for the tyrant alone of everyone else.

I would only be moderately surprised if there is no historical example of an absolute dictator publicly proclaiming this on another planet anywhere in the universe; and if there ever was such a dictator then their reign was a short-lived one.

However, this raises a paradox.

The paradox is that while the justification for the existence of all forms of government in history is inherently democratic, the real world practice of good governance is inherently elitist because only a minority of the citizenry of any nation understands policy well enough to benefit the nation-at-large by influencing policy.

This governmental paradox is equivalent to the paradox that while passenger planes are built to benefit all passengers, the vast majority of passengers are not qualified to fly planes.

Thus, the justification for a government’s existence and the best system to operate the government are two, completely different, topics.

Acknowledging the democratic assumption that justifies the existence of every government, the question turns to which method is the best way to operate government?

This is a very complex topic because, although only a minority of citizens should be involved in governmental policy, there is and always has been more than just one person in every nation who is legitimately understands policy.

How, then, to determine how narrow or broad the politically qualified portion of the citizenry is?

What is the best way to incorporate the different viewpoints of the qualified?

To settle on the right answer we will first study the oldest form of government, Monarchy, how division of powers (whether the division was de facto or de jure) operated under it, and compare the division of power in Monarchy to the United States Constitution.

A major advantage of starting with Monarchy is because of the question of how much, or little, power a head of state needs is more important than ever due to how much more powerful (by all measures of power, but especially technologically) modern governments are compared to the monarchies of old.

In the case of the Roman Empire the Emperor did not have the technological power to destroy the world with nuclear weapons.

As far as dealing with his domestic audience, the Emperor’s abilities to interfere with them were also limited by technology. For example, a Greek fisherman who paid taxes and obeyed laws normally had few interactions with the Roman state over the course of his lifetime because the Emperor had no way of monitoring his citizens on a moment by moment basis that would allow him to micromanage the lives of the law-abiding.

Roman Emperors lacked even primitive 1920s-1930s radio communication systems to influence public opinion.

Limitations for communicating and receiving information to and from the public made it difficult for Roman Emperors to so much as get a general feel for the sentiment of the people at any given time (unless they revolted) because there were no opinion polls to keep track of the public’s mood. The best sense they could get would come via interviews with and letters from regional officials giving their subjective opinion about their jurisdiction’s attitude.

Because the power heads of state wield is greater than ever before the argument is, in turn, stronger than ever that leaders should operate within a modern CEO-like system that holds their actions accountable yet gives them sufficient enough freedom to carry out their duties; but no more power than is absolutely necessary for them to carry them out.

To fairly judge the worth of Monarchism as a form of government we must first understand it. Indeed, we must even respect it, despite its various problems, because Monarchy, far from being rare, is the most common form of government of all time spanning across cultures, nations, and continents.

Giving Monarchy the due it deserves can be a difficult bias to overcome in modern times because ever since the Enlightenment the ancient concept of divine right of kings has been demoted to accident of birth.

But this sentiment risks missing perhaps the most remarkable feature of Monarchy: Its durability.

The remarkable nature of Monarchy’s durability lies not in the fact it withstood the challenge of the Enlightenment for as long as it did.

No.

What is exceptional about Monarchy is that it was not challenged much earlier than the 18th century because, on first glance, order of birth has nothing to do with one’s qualifications to perform the classic functions of government.

Additionally, from the perspective of shareholder theory Monarchy has complex coordination problems to solve before it can get other elites to become supporters of a system of government by hereditary descent.

Some of the objections preventing other elites from “buying shares” in Monarchy are –

1) Hereditary transfer of power is arbitrary. If power is awarded on the arbitrary basis of birth order then other elites, who may rightly or wrongly feel more capable of governing, would withhold their support for a ruler who, in their view, did nothing on their own to merit the position.

2) The monarch, being chosen by what order and to which family they were born into, would often be mediocre, or worse, at their job because of the law of averages. Every time a hereditary monarch stumbled their own elites would be reminded of the fact they were chosen not on capability but by coincidence. Why should a system at risk of producing unimpressive results be tolerated for so long by elites across the world?

And have no doubt that Monarchy must satisfy elites according to the principles of shareholder theory because under oligarchical spectrum theory every autocrat, including the most autocratic monarchs, has an elite of some kind that wields formal or informal veto power over their actions and which they need to please up to a minimal level to keep power.

At a minimum, every autocrat of every type must obey the military because that separate power always has the potential to overthrow any autocrat. Even at the height of his power Alexander had to yield to his commanders when they forced him to march the army back home after they refused to battle further East as Alexander wanted following his conquest of a portion of Western India.

Further complicating matters, the number of elites an autocrat has to satisfy is greater than just those in the military because no armed forces exist in a cultural vacuum. They interact with other elites such as wealthy business owners, lower aristocracy, even the commoners to a certain extent. If any of those other citizens are sufficiently upset at an absolute ruler that dissatisfaction could eventually lead to the military removing the leader, either through forced abdication or assassination.

If not even Alexander the Great was daring enough to risk completely ignoring elite opinion how, then, were far less capable monarchs able to satisfy elites for thousands of years with the seemingly flawed system of hereditary Monarchy?

Hereditary monarchs solved this problem by creating the institution of hereditary aristocracy.

Aristocrats were given “shares” in the principle of hereditary descent because their own aristocratic titles, duties and privileges (though more localized and not as expansive as those vested with the monarch) were both something they inherited from their own parents and were something they could pass on to their own children; thus literally transferring legal rights to political power in exactly the same way modern stock shares can be inherited from parents and passed on to descendants.

Thus, aristocrats usually strongly supported the monarch’s right to power through accident of birth because the power of aristocrats operated on the same principle, and anything that attacked that concept at the national scale of the monarch would also threaten their power locally.

What first appeared to be an arbitrary mechanism (order of birth) for transferring power that should, in theory, stir resentment and mistrust among elites turns out, in reality, to be a shining example of shareholder theory in action because it perfectly demonstrates that the way to win support of any system is to “give shares” to others (especially to the most influential) so they become “invested beneficiaries” in the success and continuation of that system.

By turning aristocracy into interested parties in the system of hereditary inheritance of political power a system of division of powers evolved under Monarchy where aristocrats always held some influence over the monarch. With separate power came aristocratic expectations that the monarch would grant local nobility political rights and privileges in exchange for their upholding their duties to ruler and realm.

This division of power translated into military power because aristocracy often maintained separate military forces from the national government. This arrangement was especially common in the Medieval ages in Europe and the Shogun period in Japan where the Emperor was often a figurehead with real power invested in the shoguns.

Furthermore, the existence of local militaries that were well-armed enough to cause harm to a national ruler’s forces (if not defeat them) was frequently a sufficient deterrent to prevent a monarch from revoking aristocratic rights on a mere whim; and if there was an attempt to curb the powers of aristocrats , as was the case during the Fronde, the attempt was usually costly enough to the monarch who attempted it that other monarchs would not consider doing similarly without a very cautious weighing of the risks and benefits.

Another power center almost all monarchs have had to placate is their national priesthood.

The first, major, evolution of a system of dividing power with the priests came from the Old Testament’s clear doctrine that the will of the monarch is a separate, flawed, entity from the will of an omnipotent God.

This was in stark contrast to the tendency of the pagan world to declare leaders as divine beings in practices such as Roman Emperor worship or the religious cults centered around Egyptian Pharaohs; although it must be admitted that there was great variation in the sincerity of the practitioners: The main difference between the political mentality of the Romans and Egyptians was that the superstitious Egyptians genuinely believed the Pharaoh was a living, breathing, man-god while the cynical, worldly Romans did not believe for a moment that the Emperor was a god.

The Jewish distinction between royalty and Creator eventually displaced the comfortable pagan melding of the two ideas through the expansion of Christianity.

It was the Catholic Church that led to the next revolutionary change in the relationship between church and state by the Pope becoming more politically powerful than Christian kings and emperors throughout most of the Dark ages, Medieval ages, and even managing to retain significant political pull as recently as the 19th century.

This is an important historical landmark for understanding classic division of power systems because the Pontiff’s power across national borders, which included the ability to raise armies for crusades and to excommunicate kings, turned the Catholic Church into the first international political organization in history.

Although we today are used to the existence of international organizations, what we are not used to is the existence of a powerful transnational authority that could match even a fraction of the power the Catholic Church held at its political zenith.

To fully appreciate the vast sway of the Catholic Church one would not have had to live in the early 20th century, when the Church was respected but little feared, or even the 19th century.

To grasp the full scope and magnitude of the Catholic Church as a political power one would need to have lived over 500 years ago, before the Reformation, when it was at a level like nothing a modern international bureaucrat could imagine possessing.

To have even 1% of the power of the Medieval Catholic Church is a prize that every Progressive UN and EU apparatchik in the world would happily sacrifice their first born child to Satan to gain; that is if they hadn’t sacrificed them already.

Over the course of centuries, despite periodic tensions between Monarchy and Papacy, a significant level of civilizational success was achieved wherever national power was divided with Rome.

Even though the king was not a god, Christianity tolerated the idea that the king was still nearby God as a flawed guardian of civil affairs. This created the tendency of church to divide power with the state.

Although this division of power was built more around long standing customs than explicitly written, legally binding constitutions, expectations were built around this balance that made those rules respected enough to normally be obeyed by elite stakeholders in government.

The de facto elite veto power that aristocrats, the army, and the priesthood held, and which European monarchs had to navigate, led naturally to power being divided with elite institutions.

Interestingly, the strength of institutions in monarchical systems was further enhanced by two features that would be, on the surface, thought of as weaknesses: The fact hereditary Monarchy inevitably generates mediocre, or worse, monarchs; and the act itself of raising an heir in a system of transferring power by birth order.

Monarchy has produced countless rulers who were unimpressive, if not disastrous, at their jobs because order of birth had nothing whatsoever to do with how capable they would be at governing. Fortunately, most of them were about average in the quality of their performance.

Of course, while poor performance by a monarch could negatively impact even the upper classes, mediocre leadership frequently turned out to be beneficial for elite institutions because an average monarch would be less likely to try to curb the influence of ancient, powerful, institutions by centralizing more power around the crown simply because they wouldn’t have the drive and talent to take them on.

In fact, elite institutions of the aristocracy, wealthy merchants, military commanders, and priesthood gained so much cache that they were sturdy enough to survive the occasional bad ruler. At those times when the monarch was weak, ancient institutions could assert their independent power and provide stable leadership from behind the scenes.

Perhaps the greatest advantage elite institutions had in Monarchy was the fact that hereditary rulers from birth socialized with the best members of these institutions.

Heirs to the throne were not born as coworkers with the elite. They were born as friends with the elite.

From the monarch’s perspective these friends were not merely friends.

They were the best friends possible, with access to the best people, the best parties, the best luxuries that money could buy in their time.

Naturally, this made monarchs inclined to tolerate division of powers because of a conservative inclination to not rock the boat with the elites of those power centers; elites whom the monarch had schmoozed and boozed with since birth, unless absolutely necessary.

Even strong monarchs, with the respect necessary to make major reforms, tended to not disrupt elite power centers simply because they were run by those whom they grew up and socialized with.

At this point you see why Monarchy endured for so long and why its characteristics supported the existence of divided power structures among its elites.

But it still has not been established if Monarchy is better at executing the classic functions of government, which functions are the only reason for government to exist at all.

To determine this we need to compare it to an alternative political system, an alternative that would arguably produce consistently better heads of state than selecting rulers via order of birth.

On the surface, Militocracy appears superior to Monarchy because choosing adult military leaders who had proven themselves at command should be more likely to bring competency to the role of head of state than a hereditary monarch who was simply awarded the position from birth.

However, in practice Militocracy led to unstable transfers of power because whenever there was an opening for leadership multiple generals would end up fighting for power.

This was the case in the Roman Empire which endured periodic civil wars between commanders with their own legions battle other Roman commanders for the title of Emperor.

Perhaps the most famous example of the instability of military governments was how Alexander the Great’s empire fell into a civil war fought by his own generals after Alexander died and his son died in infancy.

The advantages of Monarchy over Militocracy are clearly illustrated by how Napoleon (whom Metternich called “equally great as a statesman and as a general”) tried to solidify his rule by marrying into the Hapsburg dynasty.

At the height of his power after the Treaty of Tilsit Napoleon had the option of unilaterally creating a government based on the Revolution, a Militocracy made up of his own field marshals, or founding his own hereditary Monarchy.

The major considerations that led Napoleon to select Monarchy is embodied perfectly in the process that led Metternich to arrange the marriage between the daughter of Francis I, Archduchess Marie Louise, and the French Emperor in order to give Napoleon the monarchical legitimacy that he could not attain from the battlefield.

Before the marriage was arranged Napoleon had already ruled out the Revolution as a basis to found his system on because he no longer believed in it –

In order to judge of this extraordinary man, we must follow him upon the grand theatre for which he was born. Fortune had no doubt done much for Napoleon; but by the force of his character, the activity and lucidity of his mind, and by his genius for the great combinations of military science, he had risen to the level of the position which she had destined for him. Having but one passion, that of power, he never lost either his time or his means on those objects which might have diverted him from his aim. Master of himself, he soon became master of men and events. In whatever time he had appeared he would have played a prominent part. But the epoch when he first entered on his career was particularly fitted to facilitate his elevation. Surrounded by individuals who, in the midst of a world in ruins, walked at random without any fixed guidance, given up to all kinds of ambition and greed, he alone was able to form a plan, hold it fast, and conduct it to its conclusion. It was in the course of the second campaign in Italy that he conceived the one which was to carry him to the summit of power. ‘ When I was young,’ he said to me ; ‘ I was revolutionary from ignorance and ambition. At the age of reason, I have followed its counsels and my own instinct, and I crushed the Revolution.’

But Napoleon did not yet have a Monarchy.

At this time he had an Autocratic Militocracy with some incomplete features of Monarchy.

Napoleon had installed various family members as rulers over a number of nations he had conquered such as elevating his brother Joseph to the throne of Spain. This created a dangerous dilemma for other European monarchs who were pressured to recognize them as legitimate but feared they could not do so without undermining the principle of hereditary descent that the stability of their own thrones depended on –

Metternich, Volume II pages 277-278

September 24, 1808. — Nothing is more impossible to bring together than eternal and incontestable principles and a system of conduct adopted and followed inversely to these same principles for a long series of years.

The elevation of King Joseph to the throne of Spain is incompatible with those principles; it is more so even than that of many members of the Napoleonic dynasty, inasmuch as the means used to place him on the throne are not justified by the pretext of a right of conquest. The crown was not vacant. Nothing could less resemble voluntary abdications than those of Ferdinand VII. and Charles IV.; they were not obliged, as I had the honour to inform your Excellency lately, to sign acts of renunciation for the younger branches, therefore there still exist imprescriptible rights to this crown among many members of the reigning family; they exist in the younger branches not less justly called to the succession ; but these same rights form the indictment of all the Powers, which have recognised Napoleon in the place of Louis XVIII. That was the first, the grand usurpation ; all the others are but corollaries. The Powers, by recognising that, have admitted that they have sacrificed the principles on which their own crowns depend to imperious and secondary conditions ; but the principle has not the less been injured and the conduct of the Powers put in opposition with that same principle.

Consistent with shareholder theory, Napoleon was powerful enough that many nations, such as Sweden, wanted to “buy shares” in his Empire by marrying their royal houses with one of Napoleon’s family members, or, at least with one of his generals –

Napoleon as quoted by Metternich, Volume II pages 433-434

July 09, 1810. — ‘The Swedes absolutely throw themselves at my head. They now wish me to give them one of my marshals for a king.

They speak of Berthier or Bernadotte. Berthier will never leave France, but Bernadotte is another thing. They desire one of my relations : but there is an insurmountable obstacle — that of religion. A marshal would not mind that so much. I will show you my correpondence with the King of Sweden.’

However, this was not sufficient to create the stability required for the long-lasting royal dynasty Napoleon hoped for.

First, Napoleon would need an heir of his own who could maintain the center of the Empire from France and, by extension, from France provide enough gravity to keep his family members and their descendants on the thrones they controlled in other nations.

Unfortunately for him, his marriage to Josephine could not produce an heir because she was barren.

Another danger for his dynastic ambitions was that the Bonaparte line was parvenu. Therefore, if Napoleon died the various royals he had established would be challenged militarily for their titles by the older European royal houses in Europe that were replaced, and this challenge would be made formidable because of the greater legitimacy their older claims would hold.

Metternich described the risks of Napoleon dying without an heir, but leaving behind ambitious generals and vulnerable Bonaparte royalty on thrones whose claims would be immediately challenged without Napoleon’s formidable presence to keep order –

Metternich, Volume II page 350

April 11, 1809. — Napoleon’s fixed plan is executed. He is the Sovereign of Europe : his death will be the signal for a new and frightful revolution ; many of the divided elements will try to reunite. New princes will have new crowns to defend ; dethroned sovereigns will be recalled by old subjects ; a real civil war will establish itself for half a century in the vast Empire of the Continent the very day when the iron arm which holds the reins shall fall into dust.

Metternich suggested to Napoleon that his agreement to have Bernadotte become King of Sweden was especially concerning because giving thrones to generals could open the old Pandora’s box of generals fighting each other for royal titles

Metternich, Volume II pages 463-464

September 8, 1810. — As your Majesty speaks to me with so much openness of these things, with equal frankness I shall not conceal that I share your Majesty’s views; and I consider, too, that the precedent of a marshal being raised to the throne must exercise a bad influence on his companions. Your Majesty will soon be obliged to have one of them shot, in order to moderate the lofty ideas of the rest.

I agree most sincerely as to the undesirability of increasing the number of private individuals placed on thrones, and I think that your Majesty should consider it a great advantage to remain the solitary instance.

Napoleon. — You are right ; that consideration which is personal to me and my family, has often made me regret having placed Murat on the throne of Naples. It does not do to think of all your relations and cousins. I ought to have appointed him Viceroy, and as a rule not give thrones even to my brothers ; but one only becomes wise by experience. As for me, I ascended a throne which I myself had newly created ; I did not enter on the inheritance of another. I took what belonged to no one. I ought to have stopped there, and to have appointed only Governor-Generals and Viceroys. Besides, you need only consider the conduct of the King of Holland, to be convinced that relations are often far from being friends.

As for the marshals, you are so much more in the right, as some of them have already had dreams of greatness and independence.

But I will prove to you that in the Swedish affair I remained perfectly neutral.

The Emperor rang for his private secretary, and had all the correspondence with King Charles XIII . brought to him.

Napoleon was fully aware of the requirements for a stable royal house when he told Metternich he envied the Austrian Empire’s stability in terms of its supporting institutions which were strong regardless of who was the Austrian Emperor, whereas Napoleon’s Empire was not yet strong enough to survive without him –

Metternich, Volume IV page 435

January 24, 1828. — Since the world began, never has a country shown such an utter want of men fit to conduct public affairs as France at this day. Bonaparte was right when he said – and he said it to me twenty times – ‘They talk of my generals and my ministers ; I have neither, I have only myself! – you have not me, but you have generals and ministers better than I have!’ Without boasting, I may say that we have better men than any that France has, or has had since the Restoration ; and France has not the Emperor of the French with his good sense.

The opportunity for Napoleon to create a stable Monarchy came after France defeated Austria at the Battle of Wagram.

Following France’s victory Napoleon sent out signals to Austria that he was interested in a marriage to the daughter of Marie Louise, and divorcing Josephine in order to produce not only an heir, but an heir whose Hapsburg lineage was ancient and prestigious enough across Europe that it would negate any Bourbon claim to the throne of France.

Soon after these messages of interest were sent out Metternich’s wife attended a diplomatic reception in Paris for the wives of foreign ambassadors because Metternich was at this time Austrian Ambassador to France. There she was invited to a private audience with the Empress Josephine who informed her that she was prepared to agree to a divorce with Napoleon in order to facilitate the marriage with Marie Louise. During this conversation Metternich’s wife was warned to tell her husband that if Francis I or his daughter refused the marriage it would lead to a new war between Austria and France –

Countess Metternich writing to her husband, Volume II pages 373-374

January 3, 1810. — The next morning Madame d’Audenarde came to visit me, and told me that the Empress much wished to see me.

[…]

I had hardly recovered from my astonishment when the Empress entered, and after having spoken to me of all the events which had just happened and of all that she has suffered, she said, ‘I have a plan which occupies me entirely, the success of which alone could make me hope that the sacrifice I am about to make will not be a pure loss ; it is that the Emperor should marry your Archduchess. I spoke to him of it yesterday, and he said his choice was not yet fixed ; but,’ added she, ‘he believes that this would be his choice, if he were certain of being accepted by you. I said everything I could to assure her that for myself individually I should regard this marriage as a great happiness; but I could not help adding that it would be painful for an Archduchess of Austria to establish herself in France. She said, ‘ We must try to arrange all that ; ‘ and then expressed regret that you were not here. ‘It must be represented to your Emperor that his ruin and that of his country is certain if he does not consent, and it is perhaps the only means of preventing the Emperor from making a schism with the Holy See.’ She told me that the Emperor would breakfast with her today, and that she would then let me know something positive.

Francis I agreed to the marriage in exchange for relieving pressure on Austria’s nearly bankrupt economy, restoration of some lost Austrian territory with the possibility of gaining more later by ingratiating himself to Napoleon, permitting Austria to rebuild its military and, potentially, creating a line of Hapsburg descended Emperors who would inherit Napoleon’s Empire, thus, increasing the likelihood they would treat Austria as an ally in the future.

The marriage was very popular in France and Austria because it created hope among the public that years of war that began with the French Revolution would be replaced by an enduring peace between the two nations.

For Napoleon, his marriage into the Hapsburg line achieved his goal of creating a dynasty with sufficient legitimacy, institutional strength, and aristocratic support that could survive the appearance of an incompetent monarch, which is the true test of monarchical stability –

Napoleon as quoted by Metternich, Volume I page 152

‘I shall continue to appoint senators to all the places. I shall have one-third of the Conseil d’Etat elected by triple lists, the rest I shall nominate. In this assembly the budget will be made, and the laws elaborated. In this way I shall have a real representation, for it will be entirely composed of men well accustomed to business. No mere tattlers, no idéologues, no false tinsel. Then France will be a well governed country, even under a fainéant, and such princes there will be. The manner in which they are brought up is sufficient to make that certain.’

Now that you understand why Monarchy was in theory and in practice such an exceptionally successful and stable system for balancing the power of elites, and why its advantages were so clear to Napoleon over the adoption of Militocracy, it is time to distinguish the periodic tyranny and repression of elite institutions (and tyranny in general) in Monarchy against the tyranny and repression of elite institutions in Fascism, with Nazism being the most complete version of the latter.

It is true that nearly all monarchies went through cyclical periods of tyranny.

The difference between this tyranny and that experienced under Fascism is that in Monarchy there were structural factors that pulled them back into a less heavy-handed equilibrium over time.

One factor leading to this was that, unlike Fascism, tyranny in Monarchy was justified on an ad hoc basis because the monarch did not need to justify their power on permanent ideological grounds aside from divine right of kings (or some version of it). Monarchs would impose tyranny for transitory reasons of convenience. When circumstances or a new monarch came to power the previous reasons for tyranny would often be gone and restrictions could then be relaxed.

By contrast, Fascism was born in the 20th century, and the 20th century was the century of scientific dictatorship.

The tyranny of Fascism was based on ideology that was the foundation of the Fascist state itself.

Therefore, anyone who rose to power in a Fascist nation would be obligated to continue its oppressive policies indefinitely.

And since this ideology centralized everything around the state there would be no room for division of powers with elite institutions; all of which were destined to be merged in some manner with a central government.

Monarchy was exceptional at eventually restoring elite equilibrium after stormy periods because different, centuries old, power centers could flourish under lax rulers and set cultural expectations on future monarchs for how they should treat them.

Whenever there was conflict between the monarch and an elite institution the monarch rarely entered it lightly, and it was difficult and risky when done. Usually, restricting the rights of an elite institutions was done only on an as needed basis against one particular institution that had gotten out of line, with this reigning often reversed by future monarchs as was the case with the abolition and then reinstatement of the Jesuit Order. This was fundamentally different from the comprehensive method of Fascism with its systematic absorption of all institutions into the ruling party.

Indeed, the immediate concerns of new monarchs compared to their predecessors fluctuated so often that the idea of a “political party” did not exist in Europe until the 19th century, and did not acquire the modern connotations it does today until the 20th century.

Before the 20th century the concept of a “party” in a monarchical setting was simply an interest group of elites that had come together around a particular issue, and the moment that issue was resolved the party no longer served any purpose and was disbanded.

No less important a defense against tyranny that elite institutions enjoyed under Monarchy was the fact that (unless they were a founder of a dynasty) the monarch inherited his power from birth and did not need to fight for it in the streets like Fascists did.

Someone who is born into luxury and power, and who socializes with their cultural elite from their earliest moments will be less likely to want to overturn the cultural order they were born into because of comfort and relative lack of ambition compared to 20th century tyrants who did have to fight their way to power like ambitious young mobsters.

Fascism, by contrast, had a revolutionary character that lacked at its foundations any of the cultural constraints of tradition or long-standing personal and social ties to aristocracy and other elites that Monarchy had and which could limit Fascism’s tyranny from constant expansion, or restrict its intolerance for old monarchical institutions that insisted on having their old degree of independence.

Communism, of course, was more immediately revolutionary (and, therefore, more obviously a threat to the old monarchical order than Fascism) because of its drive to destroy the monarchical institutions immediately rather than to utterly subjugate them like Fascism, although this, too, had a few exceptions such as the Soviet Union’s decision to somewhat reverse course on religion and tolerate the Russian Orthodox Church provided that its priests were fully infiltrated by and cooperative with the Soviet intelligence agencies.

Both Fascism and Communism chose new leaders based on how well they worked their way up through their respective party systems, not by hereditary descent; with the one, unique exception to this rule being that most odd of oddballs, North Korea, which is a Communist state with a hereditary transference of power. It is literally history’s only Communist Monarchy which combines the worst of both worlds by merging the permanent ideological mindset of paranoia, eternal belligerence to its non-Communist neighbors, and the economic mismanagement of Communism with Monarchy’s awarding power not on competency but on birth order within the Kim dynasty.

But even if Communism were more interested in absorbing the ancient regime like Fascism was instead of destroying it, it would have manifested the same tyrannical tendencies because it shared the complete freedom from all constraints of tradition and custom that Fascism enjoyed.

Progressivism, like its fellow 20th century scientific dictatorships of Fascism and Communism, is also unburdened by any cultural limitations on its tyranny, although, unlike the other two, Progressivism has absolutely no common sense whatsoever.

The only thing slowing the advance of Progressive tyranny is that it has to operate in parallel with Capitalist and Democratic structures because, unlike Fascism and Communism, it does not seize control of the entire state immediately from the top. Instead it builds itself up slowly from the bottom up, one plastic straw and pronoun at a time. But its end state is equally tyrannical, although how this functions is too complicated to get into in this work because the operations of Progressivism are much more bizarre and convoluted than the more straightforward, easier to understand, systems of Fascism and Communism.

The perpetual nature of 20th century tyranny compared to hereditary Monarchy is why the dystopian state – which is the total, scientific state – envisioned by 20th century writers simply doesn’t exist in any example of Monarchy because there is no real attempt to permanently merge everything with the state in Monarchy, except on an ad hoc basis by more tyrannically inclined Monarchs, and who are rarely used as positive examples by ideological defenders of Monarchy. Hence there are no writers who parodied Monarchy as dystopias like Communism and Fascism were parodied by Orwell and Huxley.

If the total scientific state of the 20th century had existed in the past, then 1984 and Brave New World would have been written by Plato at the earliest, or by Shakespeare at the latest.

But Plato did not write 1984 and Brave New World.

Shakespeare did not write 1984 and Brave New World.

Orwell and Huxley, respectively, did because the total scientific state of their dystopian novels only reflected reality in their century.

In many ways, the reason Monarchy thrived for thousands of years while Fascism and Communism could not survive for a century (save some Communist remnants in Cuba and North Korea) is owed to the fact Monarchy had stronger institutions and different power centers that acted as moderating and civilizing influences on instincts that went completely unchecked in the absolutist scientific states of the 20th century and, as a consequence of that, burned themselves out with their expansive ambitions.

Despite its long record of success the Enlightenment eventually appeared to challenge what seemed to be flaws with Monarchy. The case against Monarchy is vast and included strong points, as well as weak ones. But for our purposes we will limit ourselves to some of the major criticisms of Monarchy that the Constitution of the United States attempted to fix.

As we compare these two systems we will see that the logic of the Constitution is actually very difficult to argue against. This is especially true of the concept of the President as set out in the Constitution of the United States when one realizes that in order to carry out the classic functions of government it is not necessary to hand a leader dictatorial powers.

To understand this we will analyze how Monarchy and the Constitution treat the head of state and how they deal with situations where the leader performs poorly.

As was mentioned earlier, it is not true that Monarchy had no mechanism to remove a bad leader as Democracies do today. In Rome, the Emperor was “impeached” through assassination by the military. Forced abdication of the throne was another option. But whether the monarch was removed by assassination or abdication they first had to create an intolerable mess before the military and other elites felt they had more to lose by keeping the ruler in place than by taking upon themselves the considerable risk of initiating a coup.

Hamilton engineered the ratification of a Constitution that would comprehensively address the powers of the head of the state.

The advantage of the President as laid out in the Constitution is that the presidency itself is structured around the limited, constrained, power model of a modern CEO.

The powers of CEOs are limited to those powers which are sufficient to run the essential functions of the business, while limited in scope enough to hold CEOs accountable to shareholders and government. For instance, CEOs can fire employees for poor performance but cannot execute them for poor performance.

CEOs are also legally obligated to handle their business in certain ways by both government mandates and mandates from corporate charters and the desires of a corporate board and shareholders. These obligations include legal restrictions on how they are paid, how their financial statements are created and released, and myriad other rules that serve as constraints on their executive powers.

If CEOs can operate effective businesses without having dictatorial power, then is it necessary for the President to need dictatorial powers to execute the classic functions of government?

The Constitution goes to great lengths to limit the President to just what are needed to perform the classic functions of government, and without any further power beyond that point.

It does so by specifying mandates and rights for all branches of government, including the rights and powers of the states.

These mandates are protected by the fact it is very difficult to change the Constitution (which can only be done by supermajorities) which prevents the President from changing their own mandate to acquire dictatorial powers that are excessive to what are needed to carry out the classic functions of government.

Beyond Constitutional mandates, the President is obligated to carry out legislative mandates passed by the Congress and any mandates created by the federal court systems.

Instead of having a coup remove a President for bad performance the President can be removed during reelection by the voters, impeached by Congress, or more severely reigned in for the rest of their presidency by an opposition party gaining majorities in Congress at the expense of the President’s party.

By creating non-violent mechanisms for removing a President, or at least constraining their behavior in, the Constitution has successfully replicated the CEO model of removing or correcting the mandate of a CEO for performance reasons.

This also consistently creates a smoother transition of power than hereditary Monarchy which was vulnerable to power vacuums that would be created if a monarch could not produce an heir to the throne, as was the case in the events that led to the War of the Spanish Succession .

The Constitution also better handles power imbalances between elite institutions than Monarchy does because the Constitution explicitly outlines what powers each branch of government holds. Monarchy, on the other hand, periodically underwent wars over rival power centers (such as conflicts between kings and popes over what power the Catholic Church had within a kingdom) because their powers were often more based on ancient cultural traditions and unwritten rules than explicit, binding, legal codes.

The Constitution’s division of powers could be considered dividing the powers that would be needed for one branch of government to overpower the others. The President, who must answer to the voters at election time, is obligated to carry out the classic functions of government as set out in the Constitution and execute any laws passed by Congress. The courts determine if the laws passed by Congress are constitutional.

While this system has not perfectly prevented constitutional crises or one branch from gaining power over the others at times, it has been better balanced, with far less violence, than power divisions in Monarchy.

It also better reflects the mandates imposed on CEOs to carry out their duties by the government, shareholders, and board members in modern corporate structures.

The Constitution also better handled the problem Monarchy encountered during the Enlightenment of the dissatisfaction of the middle and working classes with their rights, especially property rights.

The issue of rights and property rights is an example of what happens in shareholder theory when important segments of society withdraw support for a system because they are dissatisfied by how little they benefit from the system.

With the emergence of modern economies in the 18th century, and especially by the Industrial Revolution a century later, came dissatisfaction that the economic power of the aristocracy, which had accumulated wealth over the centuries along with political power, and the perception that this wealth was not earned by a middle class that was increasingly prosperous through economic development instead of through the order and family in which they were born.

This dissatisfaction with property rights among the emerging business classes led to the American and French Revolutions.

Although Monarchies, contrary to modern biases, actually recognized some form of property rights for even the poorest members of society, these rights were subject to being revoked for seemingly arbitrary reasons by the state whereas monarchs, aristocrats, and the priesthood had extra protections over their property.

To rectify this, Hamilton endorsed a Meritocracy where, unlike Monarchy which had different tiers of rights for different citizens, every American had the same Constitutional rights and property rights, with protections against their property being removed without due process in court or fair compensation from government.

These property rights were codified in the Constitution and any additional protections to property could be added through laws passed by Congress.

(As a side note, observe that Constitutional rights are not the same as Congressional legislation. In recent times there has been confusion about a lack of rights such as “a right to privacy” which does not exist in the Constitution. Their absence is then used as justification for arguing it is out of date over such things as technology. This is incorrect because the Constitution does not need to handle changes in matters such as privacy and technology. Privacy can be equally protected by acts of Congress without the creation of a Constitutional right to privacy. The legislative process is the main way the founders intended for government to keep pace with changes in society, whereas the Constitution is designed to protect the most essential rights and structure of government with finer details left to Congress. By complaining about “a lack of rights” Progressives are trying to avoid going through the legislative process in order to avoid votes that their partisans would be reluctant to go on the record supporting, and which they would prefer be “discovered” by the courts.)

The guarantee of property rights so early in the Enlightenment in 1787 is an essential reason why the United States was able to take advantage of the Industrial Revolution in the second half of the 19th century to become the most powerful economy in history.

Secure property rights allowed the business elite Hamilton envisioned as a natural ruling class, as well as foreign investors, to operate in confidence that their business interests would be protected and there was no limit to how wealthy they could become.

This Capitalist freedom operated unencumbered to take full advantage of the unprecedented economic opportunities of the Industrial Revolution.